Scientists in Juelich, Germany have switched on the world’s largest “artificial Sun” for the first time, called “Synlight”, which could be used to create useful hydrogen (environment-friendly fuels) in the future.

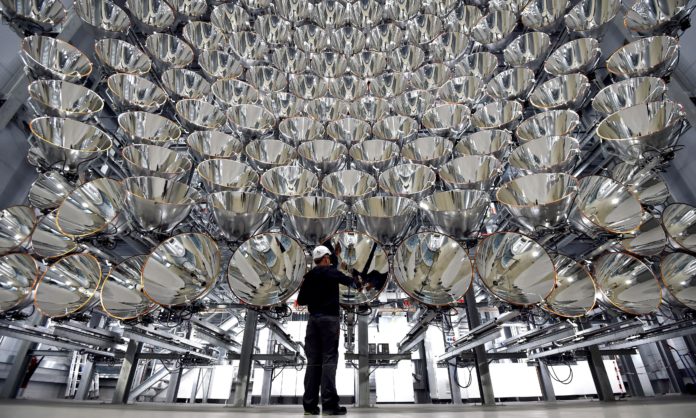

Located in Jülich, a town located 30 kilometers (19 miles) west of Cologne, Germany, and developed by scientists from the German Aerospace Center (DLR), the “Synlight” system that consists of 149 industrial-grade film projector spotlights (each one boasts roughly 4,000 times the wattage of the average light bulb) all together resembling a gigantic honeycomb. The spotlights, which are powerful xenon short-arc lamps and normally found in cinemas, that uses to simulate natural sunlight that’s often in short supply in Germany at this time of year.

“Synlight” is the largest collection of Xenon short-arc lamps ever assembled in one room, and scientists in Germany are turning them all on at once in the pursuit of efficient and renewable energy. When this artificial sun is switched on, it generates light, which is 10,000 times as intense as natural solar radiation on the Earth’s surface (while temperatures at the target point of the lamps can reach up to 3000°C). Concentrating the lamps and swiveling them on one spot can produce temperatures of around 3,000 degrees Celsius (5,432 degrees Fahrenheit), which is two to three times as hot as the temperature generated by a blast furnace.

During the launch, the researchers focused the Synlight’s 350-kilowatt honeycomb-shaped array onto a single 20 x 20 cm (8 x 8 inch) metal sheet. The director of DLR’s Institute for Solar Research, Bernhard Hoffschmidt, says the system is capable of (creating such furnace-like conditions) as high as 5,432 degrees Fahrenheit (3,000 degrees Celsius). The entire structure measures an impressive 45 feet (14 meters) high and 52 feet (16 meters) wide. In the three-storey “Synlight” building, electrically-powered sun lamps will be used for various research projects, including developing processes for producing hydrogen fuel using sunlight.

“If you went in the room when it was switched on, you’d burn directly,” Professor Bernard Hoffschmidt, a German Aerospace Center research director, tells the Guardian.

The “Synlight” researchers say the aim of the experiment is to improve the production processes for solar fuels, including hydrogen, which they believe will be an important renewable energy source in the future.

Hydrogen is considered to be an incredibly useful element, being a source of fuel of the future because it produces no carbon emissions when burned, meaning it doesn’t add to global warming. But while hydrogen is the most common element in the universe it is rare on Earth. One way to manufacture hydrogen is to split water into its two constituents of hydrogen and oxygen by using electricity in a process called electrolysis. Artificial sunlight could provide a more affordable solution in the future and help counter global warming.

Researchers hope to bypass the electricity stage by tapping into the enormous amount of energy that reaches Earth’s surface in the form of light from the sun. One area of the team’s Synlight experiment will focus on how to efficiently produce hydrogen from water vapour, a first step toward making artificial fuel for aeroplanes and cars.

DLR’s director, Bernhard Hoffschmidt said the dazzling display is developed to take experiments done in smaller laboratories to the next level, adding that once scientists have mastered electrolysis (hydrogen-making) techniques with Synlight’s 350-kilowatt array, the process could be scaled up ten-fold on the way to reaching a level fit for industry. Scientists say this could take about a decade, if there is sufficient industry support.

The artificial Sun system, “Synlight” cost a total sum of 3.5 million euro (US$3.77 million), most of which was provided by the state of North-Rhine Westphalia (2.4 million euro), with BMWi contributing 1.1 million euro (US$1.2 million).

“Synlight” currently consumes a vast amount of energy – for 4 hours of operation, it requires as much electricity as a four-person household would use in a year – but researchers hope that in the future natural sunlight could be used to generate hydrogen in a carbon-neutral way.

“We’d need billions of tonnes of hydrogen if we wanted to drive aeroplanes and cars on CO2-free fuel,” said Bernard Hoffschmidt. “Climate change is speeding up so we need to speed up innovation.”